When the Doll Speaks

Imagine, if you will, the horror one feels, when something that was never meant to have a voice screams.

You Left Me To Die

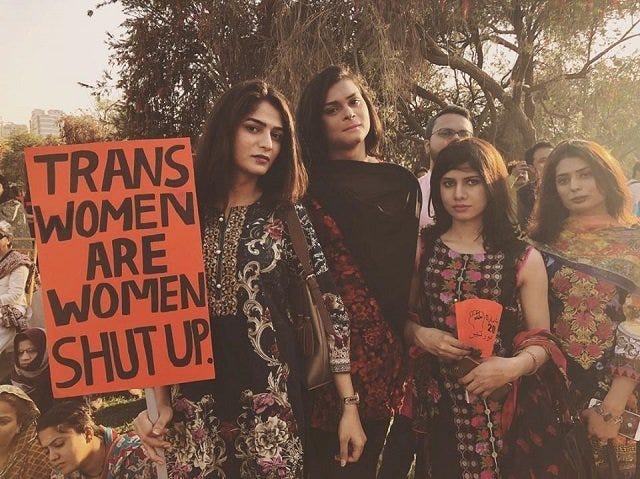

The disproportionately high rates of abuse that trans women suffer—even prior to transition—should not mystify anyone.

Consider, for a moment, how easy it is to isolate a target whose precarity is near-guaranteed. Whether we are vocal or silent about our true identities, whether we are scrabbling for hormones and desperately-needed healthcare or wasting away without them, whether we are actively taking steps to find community with those like us or never breathing a word about what we really are—even to ourselves—a trans woman is always dangling one foot out the door, hoping and praying that this time, she can step inside with both feet. Families frequently abandon and disown trans women, and just as frequently exercise more violent options. Exclusion from many economic opportunities and the twin threat of expensive care and inevitable impoverishment is ever-present. All of which pales in comparison to that singular quality which abusers covet over and above all else:

No one believes trans women.

Many factors endemic to transmisogyny underlie this denial of epistemic authority. Plenty of people choose to subscribe to the collective delusion that we occupy a hegemonic male positionality at any point in our lives, an expression of cissexist faith in the naturalization and immutability of sex that does not waver even in the face of contradictory evidence. That we are slandered sometimes with male forms of address is pointed to as a paltry, paper-thin rationalization for ignoring how we are treated instead of what we are called by those who wish to monster us. The tranny is a “man” only when she can be painted as a brutish, deluded, or perverted one. She is constructed as a threat in every instance, one so existential that her very presence justifies all manner of violence against her—all in self-defense, you see.

This is compounded by the reality of the mechanism—trans women are degendered, regarded as some kind of heinous, aberrant, nonhuman thing that must never be countenanced, only rectified. Our expressions of pain are manipulations, never sincere. Our wounds are only ever self-inflicted, likely for attention—for who would even want to sully their hands with us? Assaulted—what do you mean? Who could ever want a thing like you? You were obviously the one who tricked them. How dare you let your misshapen form be inflicted on a poor soul with their hand around your throat? You’re lucky he didn’t just kill you—and he would have had every right to, too, given what you did.

Degendering dehumanizes us utterly because a patriarchal regime conditions legibility upon gender. Are you imbued with a modicum of agency, your place in society central and venerated and deified, the sire and scion of your line? Are you a reproductive asset, a vessel through whom the actual agents of history will perpetuate their marks upon a world forbidden to you?

… Or are you, in fact, something else entirely? Something that is neither citizen nor serf, something that cannot even serve the purpose of incubator, something whose only use can be absorbing as much violence as those around her deem her fit to take?

Are you a still-shambling corpse—dead tranny walking?

I called myself that to my then-girlfriend of just two months, trying to tell her to not get too attached to me, trying to express to her that no matter how hard I tried, I’d realized exactly where all my roads led and she was better off not witnessing my arrival at the destination. That was five years ago, and I’ve never been more glad to be wrong.

Well.

So far.

Bury Me Deep

Deepa Mehta’s Fire notes that Hindi lacks even a word for the term ‘lesbian’; it has no concept for the idea of a woman who might love or carnally desire another. Under the harshest contradictions of patriarchies that view women as burdens, as liabilities whose only utility is in ensuring the continuation of male lines, the particularities of a woman's identity become immaterial. A ‘lesbian’ is a meaningless concept to a culture without any regard for women’s interiority, that orients women to a singular purpose whether they are heterosexual, homosexual, asexual, or otherwise: domestic, reproductive, and care work, effectively rendering them indentured servants and a source of uncompensated, undervalued, feminized labor. Gender is, ultimately, a labor relation, a set of rationalizations for a social paradigm of exploitation that leans on notions of biodestiny and specific embodiments being for specific purposes.

Who or what a woman loves stops mattering; it only matters that she is used correctly.

I recommend Adrienne Rich’s essay on ‘compulsory heterosexuality’ because I don’t know how to succinctly convey the feeling of panic that settles into my very core when a friend doesn’t log in for a few days, or our group simply doesn’t hear from them, leading us all to wonder—is this it? Has the regime of heterosexuality compelled them finally, press-ganged them back into womanhood and the only purpose women are deemed suited for under it? Friends have told me of fathers who force them to read scripture, who lament their shame and failure at having produced something so ‘defective’ as a ‘daughter’ that resists being married off to a man, who insinuate that these ‘daughters’ are fortunate to still live—that the continuation of their lives is in fact an indescribable act of mercy. We commiserate, we plot, we try to imagine a future untainted by a pall so heavy as to blot out all hope of happiness. Sometimes we succeed.

Just as often, we fail.

While the essay does not mention trans women explicitly, the heterosexual mandate is nevertheless scrawled all over transfeminine histories. In the West, trans women have long been held hostage by medical practitioners—largely men—who demand performances of hyperfemininity from us in exchange for desperately-needed healthcare. This healthcare could and in many places still can be withheld at any time on the basis of arbitrary “psychological evaluations”, a well-known euphemism for, to put it bluntly, our potential fuckability.

Outside the West, our destinies are even more dire, with the transfeminized being pushed to the absolute margins of society and locked out of the economy at nearly every level. This collectively imposed degendering and impoverishment is frequently justified along theological and cultural lines that credulous anthropologists from Western academies uncritically reproduce, romanticize, and weaponize. Serena Nanda’s Neither Man Nor Woman holds up South Asia’s hijra as objects of macabre Orientalist fascination, waxing rhapsodic about their “social role” as “homosexual male prostitutes” (frequently calling attention to their putative ‘maleness’ despite the book’s own title) and constantly describing their ostracism and suffering with all the detached, casual cruelty of an English children’s author. To the Western academic, the subjectivity and activism of transfeminized Third-Worlders is a distant concern next to their rhetorical utility as a ‘venerated’, vaunted “Third-Sex”, casting “primitive yet Enlightened” non-Western cultures as curious gender-practitioners from whom the West has so much to learn. All the while, the ways in which Third-Sexed populations like hijra identify with womanhood and organize for legal recognition as women are utterly elided; as Serano grimly notes of Nanda’s Gender Diversity in Whipping Girl, the “gender-diversity” of the Orientalized non-Western culture is a sacred cow for many academics who concern themselves with queerness and (supposedly) feminism, a crucial cudgel with which to beat and berate the “medicalized”, “Western” transsexual. Transition healthcare that is socio-economically out of reach for many Third World trans women is derided as “imperialism” while the transmisogynistic model of “Third-Sexing”, first imposed by our own cultures and then legitimized by Western academics, is simply considered scholarship.

Many Westerners, it seems, would happily let my sisters languish without means or care just to reinforce their own worldviews.

Even within this context, I find myself still oddly erased. Afsaneh Najmabadi in Professing Selves recounts asking a room full of Iranian transsexuals if any of them were lesbians and receiving blank stares in response, an experience consonant with my two transsexual friends being asked if they were best friends in a Mumbai cafe—by a trans woman. Womanhood is understood to be for men, transition understood as a social technology for people who wish to access particular relations to manhood. Certainly true in the Third World, if not in the West as well, given how much the global transmisogynistic panic fixates on the specter of the rapacious male dressing up in women’s garb to sexually exploitative ends. Lesbianism remains erased, buried, forbidden to cissexual and transsexual women alike, an untenable identity that many cultures refuse to even acknowledge with contempt.

I have no past, and many would have it that I aspire to no future, either.

Strains of academic feminism exist that consider colonialism to be the genesis of patriarchy, that idealize a prelapsarian pre-patriarchal past that was then tainted by the relentless scourge of worldwide Euro-imperialist hegemony. I do not know how to explain how old the misogyny in Hindu scriptures is, how the history of my people is replete with burned widows and drowned infants and femicidal practices that far predate any British law, how the hijra and khwaja sira were persecuted on the subcontinent long before the Raj, how the ‘veneration’ of holy men is not actual social capital but rather theological justification for confinement, isolation, and exclusion.

I do not know how to explain to people how many lesbians and trans women and queer people need to flee their abusive families, flee the Third World entirely if they can, because staying where they are means accepting erasure, accepting death, accepting a brutal and brutalized life in the absence of sufficient privileges or luck to shield us from how much our societies abhor those who repudiate the heterosexual-reproductive mandate.

I do not know how to explain to you that our pain matters, that our pain is real, and that our pain is important on its own merits and not as rhetorical tools furnished for Westerners in arguments about their own genders and imperialisms and blighted settler-colonial cultures.

My friend would call this hermeneutical injustice—a silence and absence of ideas, concepts, and terminology deeper than ripping out tongues or censoring presses can achieve. It is a void, an absence, an utter displacement in time and history because no one like you was ever supposed to exist, and if they did, they were buried deep.

I am an aberration, an anomaly, a paradox, and my feminism has always been a struggle to make myself legible—first to myself, then to those both of my culture and not.

It is strenuously opposed.

No Country for Failed Men

My then-girlfriend, now-wife, helped me escape my abusive home and begin my transition.

“Coming out” was not a starting point for me but a grinding halt, the beginning of an arduous five years where after overcoming the hurdles of hermeneutical injustice and learning about transition well into my 20s—and realizing that transition was something I personally wanted even later—I was trapped by my circumstances with no access to hormones, no independent finances, and no ability to actually act on my realization. I had consigned myself mentally and emotionally to a slow march to my own dirge, trying to make peace with drowning slowly in a household, society, and nation that would never allow me to be what I truly am. My wife is not merely a life raft, she is the very air in my lungs, oxygen pumped into a failing heart that allows it to beat anew. There is a reason that my first fiction novel is about the liberatory potential of queer love, about finding freedom in each other’s arms.

We are not all so lucky.

Luck played a massive part, as did privilege—I do not and will not deny that. Even still, there are many whose impression of Third World migrants is a caricature, a homogenized impression that I am frequently collapsed into. It is undeniable that many legal immigrants to the West are self-selected from among the most affluent of their states, those with the means to successfully navigate the harsh border regimes imposed to keep us in our place. It is also true that diasporic politics often straddle the contradiction between “progressivism” against racialization that targets them in the West and the “conservatism” enjoyed by the comprador classes in the motherland. This does not mean that every one of us can comfortably be smeared as innately reactionary or classist. Many of us from the Third World are displaced in space as well as time, deprived of homeland and history on the basis of our queer identities. Fortunate though I was to find asylum with my wife, it is a happy accident too many of us are denied. Too many of us are not as lucky as I would wish us to be, and the world we inhabit should not be so cruel as to demand we roll the dice to escape our own extinction.

Nor is it truly an escape from the relentless scourge of patriarchy, only a modification of form and character, of going from one state of abjection to another that is less intense in some ways, more intense in others. Moving to the West granted me the ‘privilege’ of being able to embody my queer identity more openly, of adopting the signifiers and cultural markers of queerness in a language that my tongue was forced to acquire fluency in and a society that enriched itself by feasting upon my people’s blood. In exchange I am racialized, a second-class citizen twice over by dint of both my precarious legal status and the racialization that I am now subject to, that now marks me as Other. While I trust my wife completely, it is in fact alarming that my status in this country is utterly dependent on her. Immigrant women from the Third World are frequently abused by partners wielding the precarity of their legal status over their heads. In order to escape one abusive household I’ve had to make myself susceptible to abuse in another, have had to rely even more heavily on goodwill and fortune.

All to exist openly in a society that still reviles me and those like me and whose wealth is founded upon the untold and uncountable atrocities that constitute my nation’s past. I recall having a panic attack the first time my wife took me to Cambridge. I could see bloodstains on the flagstones.

That precarity has been compounded by my sudden unemployability. After being unable to secure adequate healthcare for my disability on the NHS—I did not even bother attempting to seek transition-related healthcare—I was forced to resort to the expensive yet still-flagging private sector and was unable to retain my job. Since then, despite an increase in qualifications, and despite no longer needing sponsorship, I find myself unable to secure more than first-round interviews, whereas a fictional man with my legal name had frequently managed to get to the third round for positions that now turned their noses up at me. Transition does many things, and one of the things it does best is erode fortunes, no matter how robust. We have been subsisting on my wife’s disability benefits.

Despite this, I am still in a more secure position than most of my kin, if only through the generosity and acceptance of my in-laws. I still do my best to help others and I make a point of not asking for help myself when so many more aren’t as fortunate as I have been. My life hangs by a thread, but at least that thread is golden; I worry greatly for those without the ‘privilege’.

So I stand, cleft from two cultures that revile me, one whose abuses I had to flee from and one whose abuses I have no choice but to subject myself to. My feminist theory is explicitly from this perspective, adrift in these currents, where I do my best to shout over the din and give name to the ways in which my identity, my experiences, and my epistemic authority are all erased to serve others’ ends.

Often, I feel alone. Until recently, I didn’t feel that quite so keenly—had thought I had found comrades and sisters and fellow-travelers, people who understood. People who wouldn’t subject me to the particular process of dehumanizing invalidation I have grown so used to in spaces both online and off.

I know better now.

I Tried

It started as a small Discord server for those who enjoyed my writing.

Author Discords are relatively banal, informal spaces. A few of my friends have modest ones, with some having truly gigantic ones, but I never expected mine to be particularly sizeable. My fiction debut had been a modest success by indie standards but it still did not mean any degree of significant reach. Several people hopped on when I shared the invite link on social media, and several of my friends did as well.

Predictably, perhaps, my Author Discord did not remain an Author Discord for long. I enjoy writing fiction and I enjoy producing the sorts of narratives I personally wished I could have seen growing up—narratives that regard lesbians and trans women as whole people with complexity and internality. Even so, my true passion has always been feminism, so much so that it undergirds even the fiction I write, informs the way I construct narrative arcs and address themes. More and more people asked to join not because of my self-published book, but because in the process of socializing and interacting with friends on the server, I could not stop discussing feminism and feminist theory. The channels about my writing languished while the singular ‘feminism’ channel expanded, and the server slowly began to look more and more like a transfeminist forum. Eventually, it somehow acquired a reputation as one too, even as I still mostly considered it an informal, social arena.

An interesting dynamic that cropped up was the sheer number of demands that were placed upon me by those in the server, while a bizarre degree of resentment and vitriol began to swell amidst some who were not. Strange accusations of exclusivity, reactionary sentiment, and imagined goings-on were fielded publicly, while privately the space remained an avenue for me to organize watch parties, speak to my friends scattered across time zones, and discuss the feminist theory I was familiar with and that I wanted to write. Over time, more and more was asked of me with regard to formalizing the pursuit of feminist work, feminist readings, feminist discussions, feminist writing—all of which was expected to fall upon me. The demands were many, the offers to assist few.

I found myself, once again, at the nexus of simultaneous monstering and pedestalization. Those who felt slighted for reasons I cannot fathom felt comfortable declaring me a fascist (due to my nation’s current regime—which I had to flee) or accusing me of uncritically regurgitating Second-Wave orthodoxy without actually pointing to my writing or my work to substantiate such claims. The ‘ontological immaturity’ and ‘conservative character’ of lesbian feminism were held forth as a charge that I was viciously berated for repudiating. Queer people from the first world—some trans, some even trans women themselves—searched for a justification to fit their distrust or disagreement. I could not be someone with a differing ideological approach or a unique perspective—there had to be something about me that rendered me secretly a bad actor, an evil radfem with ill intent and malicious designs, all for my nefarious goal of taking a materialist approach to transfeminist theorizing, explicitly from my point of view as a trans lesbian who survived Third World patriarchy.

A white trans woman told my girlfriend privately that I was the “angriest woman on the internet” and a “rage demon”. It is not the first time brown women like me have been painted as uncaring aggressors from whose rampaging excesses more-delicate women need to be safeguarded.

Meanwhile, I was being asked to do more and more in the server, things I wanted to do but found difficult to keep up with in the face of bad-faith racialized attacks from my own “community”. The need for engagement with more strains of feminism was repeatedly stressed to me, without which could I really speak on topics pertinent to my own life and the lives of women like me? I was asked to know everything and share my expertise; folks would not so much as arrange discussions they wanted to have of their own volition but would ask me to organize and prioritize and plan at their behest.

Not once was it ever asked whether my work could have merit without existing in conversation with every other strain of feminism, several of which treat the oppression of Third World women as a rhetorical abstraction. It was taken as a given that anything I had to say could not possibly have value on its own merits, that my perspective as a trans lesbian from the Third World could not possibly stand on its own. Being in conversation with other schools of thought is integral to scholarship, but I was not asked to be in conversation with others—I was told in no uncertain terms that my own work would not be adequately progressive, would somehow fall prey to reactionary tendency, unless I deprioritized drawing on my own culture’s patriarchy and my own empirical observations and subordinated my own life’s work to the prevailing orthodoxy.

I was, frankly, being asked to deny my own epistemic authority, specifically to center and engage with work that has long neglected women like me.

That is, ultimately, the rub. Due to the erasure of women like me—transfeminized, lesbian, of the Third World—due to the epistemic injustice we are subject to, it is easy for others to define me, to construct a phantasmatic apparition whose sins I can be held accountable for. Neither those who denounced me nor those who sought to extract more and more labor from me truly saw me as a person, only something to instrumentalize, to repurpose to their own ends.

I am a brown trans dyke from the global south, and women like me are not supposed to speak for ourselves.

So I acquiesced and, deleting the server and my online presence, I fell silent.

Feel My Pain

Because women like me are reduced to tools for others to exploit, it is easy to vilify us when we do not allow ourselves to be exploited. My country is the world’s sweatshop and brothel, an impoverished nation riddled with contradictions and harsh conservative regimes. My sisters are exploited by their “fellow” men as my nation is exploited by the hegemonic worldwide economic order, avenues for cheap labor both. When we are recognized, it is an Orientalized recognition, an exotified caricature of our practices or cuisine or women. Even the transmisogyny of my society, that so brutalizes transfeminized populations, is considered a fascinating and core aspect of our culture held up beyond critique.

So when we do not follow a Westernized script as Third World women, or a patriarchal script as transfeminized women, we are treated as broken dolls, as things contravening our intended purpose, fit only to vent upon and discard. Our lives become a repeating pattern of trying to find those who will not subject us to this, who will see us as people and not resources to mine. We are constantly threatened with masculinization, sexualization, demonization, and easily-achieved ostracism and social isolation from communities that only ever valued us as rhetorical mouthpieces and grew displeased at our temerity to express and insist upon our own viewpoints.

All of which is an inseparable miasmic slop that I cannot disentangle any more than I could part the sea. I cannot tell you where the racialization ends and the transmisogyny begins, which bit was in opposition to me as a lesbian feminist who refused to let her identity be disparaged and which bit was just because I was a Third Worlder speaking out of turn and refusing to let Westerners romanticize my “gender-enlightened culture”. None of it, no single aspect of me was acceptable to those who would prefer that my existence hew to a simple narrative, or otherwise fade away entirely.

Which I refuse to do.

I do not know how to explain to you that my pain matters, that I spend every moment agonizing over how best to draw people’s attention to the plights of queer women they would much rather forget. I don’t know how to explain to you that patriarchy is not a uniquely Eurocolonial invention, that my sisters and foremothers have been sacrificed on the altar of manhood for aeons and will continue to be unless it is stopped. I do not know how to explain to you that the West, whether protagonist or antagonist, wishes to be the absolute center of history, and it is decidedly not.

So I won’t bother.

I will keep working, I will keep speaking, and I will scream and scream and scream until I am heard, or until someone has the guts to silence me for good. What I have to say matters. Undoing the erasure of women like me matters. We are not your dolls, we are not your props. Our. Pain. Matters.

There is a future for people like me, and you will simply have to live in it.